Before Batman, before Superman, before even the Phantom, there was the Golden Bat. “Ogon Batto” (as he’s known in Japanese) is, arguably, the world’s first costumed superhero. The skull-headed, ruff-wearing, sword-wielding hero’s backstory was one that would fit in any of the wackier comics that Marvel and DC would later publish: He was a dweller of Atlantis from 10,000 years in the future, and sent back in time to fight injustice. In particular, he battled against Nazo, the evil Emperor of the Universe.

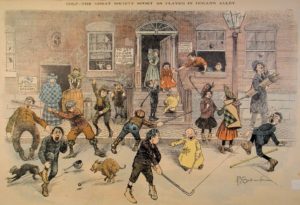

Golden Bat wasn’t a comics character. Not exactly. He was from a form of storytelling called “kamishibai,” a words-and-pictures form of public performance popular in Japan during the first half of the 20th century. Kamishibai storytellers would set up in public spaces and tell tales of samurai, ninja, pulp heroes, cowboys, and superheroes to crowds of eager children, thrilling them with outrageous tales from the worlds of history and science fiction. The medium produced, among other characters, the Golden Bat, a superhero who proceeds Clark Kent by almost a decade.

Related Links:

A contemporary example of kamishibai. It is, obviously, in Japanese.

The Golden Bat’s theme song from his later anime appearances.

Manga Kamishibai by Eric P. Nash, which collects multiple kamishibai tales from the Golden Bat and others.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: